It’s unthinkable now to imagine products being sold promoting radioactivity as good for your health. But that was the reality in the early 1920’s. At the time, the effects of radiation on the human body were still unknown. And even when researchers started to discover that radiation could harm us, these findings were not available to the general public. With this mindset, it’s easier to understand the Radium Girls saga.

After the discover of radium by Marie and Pierre Curie there was a lot of excitement about it. The properties of radium astounded scientists with its ability to glow in the dark and radiate heat.

Very soon, it was discovered that radium shared properties with X-rays and were capable of burning the skin. It then became popular the use of radium to burn off lesions, wart and cancers. The first experimenters even believed that, besides destroying morbid cells, they promoted the growth of the healthy ones. And that was the problem. They believed it was good, but there wasn’t enough research and data to prove it at the time.

That’s when the “radium euphoria” began. Companies, taking advantage of this euphoria, began to sell products that supposedly contained radium. In fact, despite advertising products containing radium, not all of them contained it because radium was a very expensive product. Due to the lack of knowledge at the time about the harm that radiation brought to health, these products became very popular.

Some products that were sold in the early 1900s

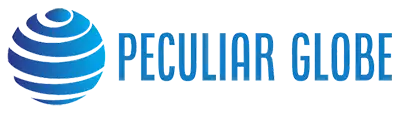

Radithor

Radithor was a triple-distilled water containing radium. It was advertised as “A cure for the living dead” and claimed to cure impotence and other diseases.

A wealthy american industrialist, Eben Beyers, died in 1932 due to the consumption of Radithor. When his body was exhumed in 1965, his remains were still radioactive. His death led to the strengthening of the FDA’s powers and the demise of the “miraculous radium era”.

The bottle of Radithor from the picture is displayed at the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History in New Mexico, USA.

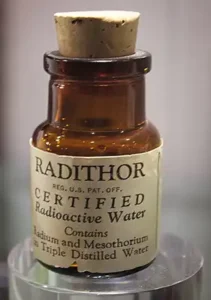

Poudre Tho-Radia (facial powder)

“Tho-radia powder” box, “based on radium and thorium, according to the formula by Dr Alfred Curie”, on display at the Musée Curie, Paris, France.

Tho-Radia was a french pharmaceutical company manufacturer of cosmetics. Many of their products were notable for containing radium and thorium, exploring the popular interest in radium at the time. Alfred Curie was a doctor with no connection to Marie and Pierre Curie. They even considered legal action against the company.

The assumption was that the cosmetic products, when mixed with radium, would stimulate living cells and increase their energy, even though nothing was actually scientifically demonstrated.

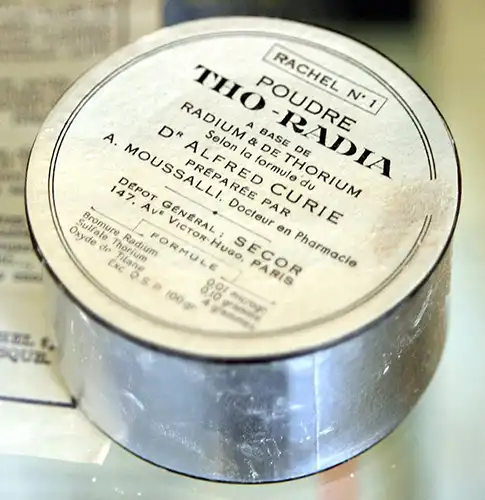

Radium ore Revigator

The picture shows a Revigator ad from the 1930s.

Revigator was a ceramic pot lined with radioactive materials. The instructions for use said that the pot should be filled with water abd leave it overnight, so that the water could be irradiated. Drinking this water would help prevent several diseases such as arthritis, flatulence and senility.

It was marketed as a healthy practice and the advertisement was so successful that the company was unable to keep up with the demand.

Radium Luminous Material Corporation

Luminous Paint

From 1917 to 1926, Radium Luminous Material Corporation (the name was changed in 1921 to United States Radium Corporation) extracted and purified radium from carnotite ore to produce luminous paint. They called the paint Undark because objects painted with it would glow in the dark. The plant was located in Orange, NJ, USA, and was a major supplier of radioluminescent watches to the military.

The paint was most used to paint watch faces and instruments. The process was all manual and workers, mainly women, were mislead into believing that the paint was safe.

Advertisement for Undark, 1921

Even though the chemists at the plant used lead screens, tongs and masks, approximately 70 women worked handling radium and the paint without protection. As the paint didn’t come already with radium, each of the painters mixed her own paint in a small recipient and then used it to paint dials with a camel hair brush. Because the brushes would lose shape after a few strokes, supervisors would tell the girls to point the brushes with their lips or tongues, what then became known as “lip, dip, paint”.

They were told many times that there was no harm in the paint. They would even paint their nails, teeth and faces for fun so they would glow in the dark.

They became known in the city as Ghost Girls. This happened because, after a day of work, they glowed in the dark. This happened because the air in the plant was always contaminated with radium dust that ended up sticking to the girls and their clothes.

Radiation Poisoning

Over the years, the girls started having health problems. The first problems were dental pain, loose teeth, lesions, ulcers, and failure of tooth extractions to heal. The dentists who would attend the girls could not understand what was happening. Then the girls started having other conditions like anemia, bone fractures, suppression of menstruation, sterility and necrosis of the jaw, a condition now known as radium jaw.

The first dial painter died in 1923. Right before her death, her jaw fell away from the skull. By 1924, around 50 girls were sick and a dozen had died. Different causes of death were attributed for them. Even syphilis was used to explain the deaths. This was an attempt by the company to destroy the women’s reputation. Since the beginning of their health complaints, the company has always denied that the radio had anything to do with it. They also influenced doctors, dentists and researchers who complied with requests from the company to not release any data.

Facing a downturn in business because of the growing controversy, the company hired and independent study of the matter. The results confirmed the girls allegations: they were dying from the effects of radium exposure. But the company didn’t accept the results and commissioned other studies that came with opposite results. And the public continued to believe that radium was safe.

In 1925, pathologist Harrison Martland developed a test that proved that the girls were poisoned with radium. The industry tried to discredit his findings but the girls fought back.

Dial painter Grace Fryer decided to sue and was joined by Edna Hussman, Katherine Schaub, Quinta McDonald and Albina Larice. It took them two years to find a lawyer who would be willing to take on U. S. Radium Corporation. His name was Raymond Berry. The litigation process moved too slow and the women were getting worse. They had their first appearance in court in 1928. Two of the women were bedridden and none could raise their arms to take an oath. The media soon was all over the case and the five women were dubbed the Radium Girls.

Even with the suit, the company continued denying its role in the women’s condition. Many of them were dying and didn’t have much time to live. So they were forced to accept an out-of-court settlement.

Radio painters working in the factory

Radium Dial Company

Located in Ottawa, IL, USA, the Radium Dial Company studio started operations in 1922. They also painted dials for clocks, most of them for their biggest client Westclox Corporation. They also hired women to paint the dials using the same “lip, dip, paint” approach as the Radium Corporation workers. By the time the girls in Ottawa started getting sick, Radium Dial authorized physicals and other tests to determine if their employees were intoxicated with radium. They never gave them the results.

At that time, the girls were unaware of the hearings and trials in New Jersey.

In an attempt to stop the use of camel hair brushes, but without telling the girls the reason, management introduced glass pens with a fine point. The glass pens slowed production. As the girls were paid by the piece, they reverted to using brushes.

Finally, when word of the New Jersey suits hit the local newspapers, the company told the women that the paint used in New Jersey was different, and that radium was safe.

In 1927, employees started to ask for compensation for their medical and dental bills but management refused it. This demand continued until a suit was brought before the Illinois Industrial Commission (IIC) in the mid 1930s. In 1937, Catherine Wolfe Donehue, along with four women, found an attorney, Leonard Grossman, to represent them and sue the company. By this time, Radium Dial had closed and moved to New York. But it didn’t stop the suit and the IIC ruled in favor of the women. The women were awarded an annual pension for the rest of their lives.

The Radium Girls legacy

The women’s fight holds an important place in the history of health physics and labor rights. As a result of their case, it was establish the right for individual workers to sue corporations due to labor abuse. The case also influenced the establishment of OSHA (Occupational Disease Labor Law). OSHA works nationally against labor abuse, reducing deaths from work-related illness and injury.

Bibliography

- Liquid Sunshine: The Discovery of Radium – Dartmouth Undergraduate Journal of Science – https://sites.dartmouth.edu/dujs/2008/02/21/liquid-sunshine/#:~:text=Marketed%20as%20a%20cure%2Dall,liquid%20sunshine%E2%80%9D%20(2).

- The lethal legacy of early 20th-century radiation quackery – Washington Post – https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/the-lethal-legacy-of-early-20th-century-radiation-quackery/2020/02/14/ed1fd724-37c9-11ea-bf30-ad313e4ec754_story.html

- History of radiation therapy – Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_radiation_therapy

- Radioactive quackery – Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radioactive_quackery

- Radium Girls: The Women Who Fought for Their Lives in a Killer Workplace – Britannica – https://www.britannica.com/story/radium-girls-the-women-who-fought-for-their-lives-in-a-killer-workplace